Potentiality of neurobiological markers associated with psychopathy being predictors of incarceration for violent crime

Shuyi Xia

Grade 11

Presentation

Problem

Because of the tendency towards aggression and violence by psychopathic populations, this study aims to find out if populations that actually commit more violent crimes than other groups have similar attributions and characteristics compared to psychopaths.

Such potential connection can be used to answer the research question, “Are psychopathic traits that are linked to neurobiological abnormalities of the brain risk factors associated with disproportionate incarceration for serious violent crime of different sexes and different age cohorts?” This study first hypothesizes that a) there is a significantly higher incarceration rate of violent crimes by a) young age (12-17, 18-24) compared to older populations (age 25 and over); b) male sex compared to female sex. Moreover, this study further hypothesizes that there is a significantly higher rate of incarceration (due to violent crimes recividism) of psychopaths compared to non-psychopaths.

This study, as a short-term objective, aims to reveal a potentiality that some common neurobiological abnormalities of the brain are risk factors for higher violent crimes involvement. Through analysis of previous literature, this study also strives to reveal examples of several potential neurobiological characteristics that, as established by previous studies, are associated with higher violent tendency. In the long term, this study endeavors to recognize the involvement of psychopathic individuals in violent crimes, raise public attention on psychopathic populations, and raise interest in further research and studies on psychopathy treatments that reduce psychopathy’s involvement in violent crime.

In Canada, there is currently a lack of statistics and scholarly attention on the research of psychopathy and its involvement in violent crime. Even though there are Canadian scholars, such as Dr Robert Hare, that examined the diagnosis and traits of psychopathy, psychopaths’ tendency towards violence and aggression, which is reflected in their involvement in violent crimes, are relatively neglected in the Canadian correctional services and prison systems. This study suggests there are many potential connections between certain biological traits and psychopathy and violence. If this study actually suggests there could be such a potential connection, this study will further encourage more research into psychopathy treatments to reduce violence tendency: since there could be a biological cause of crime and violence, treatments to mitigate the effects of these biological causes would be best to start as early as possible. Currently, most correctional services implement psychopathy treatments after the psychopathic individuals have already committed to actions of violence; such treatments include psychotherapy and behavioral skills training. However, due to a potential biological cause of crime - as this study will potentially suggest - psychotherapists, medics, and researchers may be motivated to discover more effective treatment methods for psychopathy that start at an earlier age in order to cope with the natural, biological influence of criminal and violent behaviors.

Furthermore, if this study suggests a potential connection between some certain biological traits and tendency towards crime, it will also provide essential and innovative insights into fields other than criminology alone, such as social justice, correctional services, and law enforcement. This connection between biological traits and violence can be influential in criminal courts, as such results can potentially be used by criminal defendants during trials and in courts. Previously there have been cases where such biological attributions for criminality have been taken to criminal court in an attempt to reduce the sentence of the defendant. For instance, in 2021, the New Mexico Supreme Court did not accept the defense of the defendant Anthony Blaz Yepez, who committed a case of murder years ago. The defendant’s defense was that Yepez had the “warrior gene,” the MAOA gene, which makes him more impulsive and reckless and is linked to violence. Eventually, the court ruled that caution should be taken when using biological traits as part of a defense (Nakamura, 2021). In light of such applications of biocriminology, few literature have already been discussing the applicability of the biology of crime, such as the study by Glenn et al. (2014) that provides insights into the implications of such application (Glenn & Raine, 2014). Due to the possibility of such social applications of the results of this study, more research and studies in other academic fields (law, for instance) can be encouraged to ascertain the applicability of such criminological findings, such as the legitimacy of biological causes of crimes as defense in courts, how the criminal justice system can identify high risk groups for crimes, and how such biological causes will affect the courts’ ruling. These are all significant and possible impacts of this and many other research that strive to reveal an association between violence and biology.

Method

Procedures

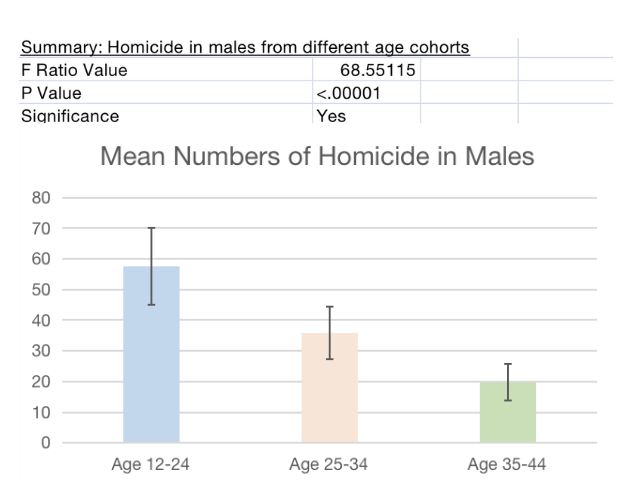

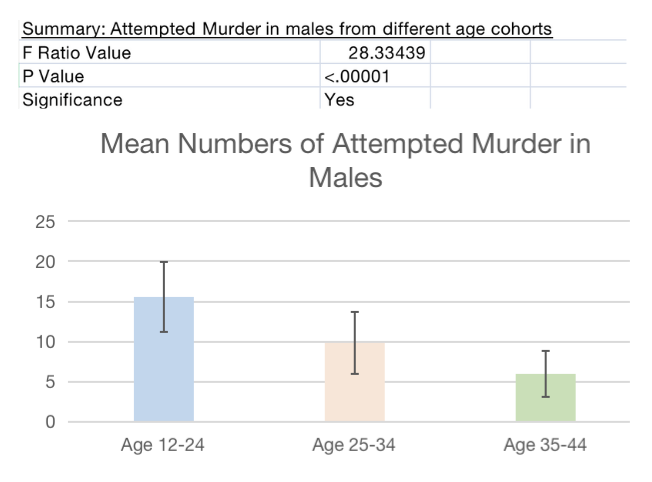

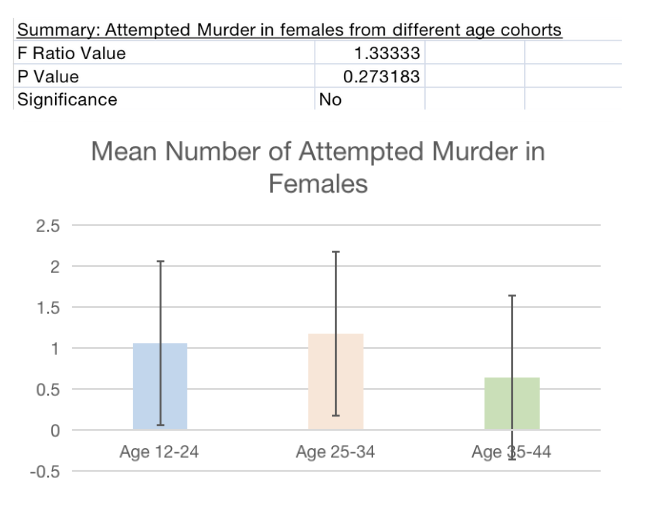

Firstly, the number of violent crimes committed by young populations and those committed by other age groups and the number of violent crimes committed by males and females was extracted from Statistics Canada (Government of Canada and Canada 2023; Government of Canada and Canada 2023). To test whether males commit significantly more violent crimes than females, an analysis of variance (ANOVA) test was conducted to compare the number of violent crimes by the two sexes. Three major categories of violent crime were investigated: homicide, attempted murder, and robbery. Data on the number of homicides, attempted murders, and robberies committed by youths between the ages of 12-17 years was extracted from Youth Court data from Statistics Canada (Government of Canada and Canada 2023). Number of violent crimes by youths (both males and females) aged 12-17 was afterward combined with data on the number of violent crimes committed by adults (both males and females) aged 18-24 years, which was extracted from Adult Criminal Court data from Statistics Canada (Government of Canada and Canada 2023). Violent crime counts committed by adults (both males and females) of age 25-34 and 35-44 were also extracted from Adult Criminal Court data from Statistics Canada (Government of Canada and Canada 2023). In each type of violent crime examined (homicide, attempted murder, and robbery), age was held constant at 12-24, 25-34, and 35-44, and the violent crime counts of males and females were compared. This statistical comparison was completed by conducting several ANOVA tests to effectively analyze whether the means of the number of violent crimes committed by different sexes from the same age cohort were significantly different statistically. To compare the difference in violent crimes committed by youths and adults, for each category of violent crimes examined (homicide, attempted murder, and robbery), data on violent crime counts of youths aged 12-17 was extracted from Youth Criminal Court data, and violent crime counts of adults aged 18-24, 25-34, and 35-44 were extracted from Adult Criminal Court data from Statistics Canada (Government of Canada and Canada 2023; Government of Canada and Canada 2023). The violent crime counts of youths aged 12-17 and young adults aged 18-24 were combined, and ANOVA tests were conducted to compare the differences in the means of violent crimes committed by offenders aged 12-24, 25 to 34, and 35-44 when the sex is held constant.

To find out if psychopaths are significantly more likely to persist in violent crimes and commit violent recidivism compared to non-psychopaths, data was extracted from Serin (1996) on the number of violent recidivism committed by a sample of 81 offenders (Serin 1996). In the study, psychopathy Checklist-Revised (PCL-R) was used to determine psychopathy among the 81 offenders. Offenders who scored 29 or greater are defined as psychopaths, those who scored less than or equal to 16 and those who scored between 16 and 29 were defined as non-psychopaths and mixed group, respectively (Serin 1996). To determine whether psychopaths and non-psychopaths are equally likely to violently recidivate, a Fisher’s Exact Test was conducted to compare violent reoffense counts by psychopaths and non-psychopaths.

To determine whether young offenders under the age of 25 were equally likely to offend as psychopaths, data was extracted from Stewart et al. (2019), a research publication from the Correctional Service of Canada (Stewart et al. 2019). The data include the rate of violent recidivism committed by young offenders aged less than 25 and between the ages 35 to less than 40. Data on the rate of violent recidivism of psychopaths were extracted from various previous literature. The rate of violent recidivism by male psychopathic offenders was extracted from studies in 1988, 1992, and 1995 (Hart et al. 1988; Hodgins et al.; Serin and Amos 1995). The rate of violent recidivism by psychopathic offenders in general was extracted from a Swedish study completed in 1999 (Grann et al. 1999). Female psychopathic offenders’ counts of violent recidivism were also extracted from previous literature by Hemphill et al. and Loucks et al. (2001) and included in the data analysis of this study (Hemphill et al.; Loucks et al. 2001). The mean of the rates of violent recidivism of psychopaths, as extracted from different previous studies, was calculated. Furthermore, the mean rate of psychopaths’ violent recidivism rate was compared with the rates of violent recidivism of offenders aged less than 25 and between ages 35 to less than 40. This was done through a Fisher’s Exact Test, which would suggest whether psychopaths and federal offenders (aged less than 25 and between age 35 and less than 40) are equally likely to persist in violent crimes.

Research

Introduction

Criminal behaviors differentiate among themselves in severity and social influence (Raine, 1993). Among the most socially impactful and damaging to the public is violent crime convictions, which usually involve the use of violence against other individuals (Definitions, 2010). Taking Canada as an example, previously the country has been measuring the overall crime rate - which includes both violent and non violent crimes - with the Uniform Crime Reporting Survey (UCR) that demonstrates criminal incidents reported by police (Crime Statistics - Crime Severity Index, n.d.). However, previous methods of crime data collection has limitations on its ability to reflect upon the severity and the trend of crime severity, as around 40% of crimes reported by police are relative minor offenses; thus if the rate of such minor crimes and mischiefs demonstrate a trend of decrease, the overall crime rate would likely to be declining as well, even if rate of violent crimes that possess more serious and harmful effects to the public is on an increasing trend (Measuring Crime in Canada: Introducing the Crime Severity Index and Improvements to the Uniform Crime Reporting Survey, 2009). The reason why violent and severe crimes such as murder, manslaughter, and rapes are not adequately reflected by prior methods of crime data collection can be attributed to violent crimes’ lack of abundance (Measuring Crime in Canada: Introducing the Crime Severity Index and Improvements to the Uniform Crime Reporting Survey, 2009). As a response, the Crime Severity Index (CSI) places a focus on examining a continuous trend of severity of crimes reported by police, addressing previous limitations. As shown in Table 1, between the years 2000 and 2022, the Violent Crime Severity Index has shown limited change, even though it has fluctuated throughout the 22 years (Government of Canada & Statistics Canada, 2023).

Table 1: Change of Crime Severity Index and Violent Crime Severity Index from 2000 to 2022 (Government of Canada & Statistics Canada, 2023)

While most would assert the presence of some psychological or psycho-pathological issues developed by those violent crime offenders who commit murders and violent assaults to their victims, other research has indicated biological and natural factors involved in their proneness to serious crime (Gao et al., 2010; Ishikawa et al., 2001; Raine et al., 1997). The debate lays on whether their tendency towards violence can be attributable to “nature” or “nurture”. Namely in Canada, it has been found that there is a “substantial proportion” of psychopaths among general criminals, ranging from 18% to 40% (Forum on Corrections Research, 2007). It is important to note that this data from Correctional Service Canada only examined the rate of psychopathy among all general crimes while it would be very likely that psychopathic individuals constitute and can be held responsible for a majority percentage of violent crime offenders. For example, as demonstrated by a research from Sweden, “the distribution of convictions was highly skewed”, with 1% of the total population who are “persistent violent offenders” being accounted for 63.2% of all violent crime convictions (Falk et al., 2014).

While the debate of nature versus nurture is still proverbial, an increasing number of neurocriminology and related research have discovered a link between proneness to violent crime and underdevelopment or abnormality in general of biological characteristics that differ from those of normal control groups non-violent and non crime-committing individuals (Gao et al., 2010; Ishikawa et al., 2001; Raine et al., 1997).

In 1997, British psychologist Adrian Raine completed Positron Emission Tomography (PET) scans on the brains of a sample of 41 convicted killers, comparing their brain images with those of normal control groups of similar age (Raine et al., 1997). Both groups were asked to press a response button when the letter “o” was seen on the screen, an activity that aims to activate the prefrontal cortex. The prefrontal cortex, located in the frontal lobe, serves to regulate thoughts, actions, and emotions (Arnsten, 2009). Furthermore it is also responsible for emotions and realizations of self-awareness, ability for complex planning, problem solving, learning, memory, and executive functions such as decision making (Renard et al., 2017). In the brain scans displayed in Figure 1, colors such as red and yellow represent areas of high glucose metabolism while colors such as blue and green indicate low brain functioning. The PET scan of normal control on the left shows strong activation in prefrontal and occipital cortex, located respectively on the top and bottom of the image. However, for the murderer’s PET scan on the right side, while there exists an activation in the occipital cortex, a “striking lack of activation in the prefrontal cortex” is noticeable (Raine, 2014).

Figure 1: PET Scans of individual without violent offense (left) and murderer (right) (Raine, 2014)

Raine indicated such lack of activation of prefrontal cortex is unique as a characteristic of murderers; other psychological abnormalities may also possess a lack of activity in the prefrontal cortex, but they are accompanied by other neurological attributions, such as “right temporal and right parietal deficits” for schizophrenics (Stoddard et al., 1997). Such traits in prefrontal cortex, as Raine argues, can be accounted for several features of murderers as it results in generation of “raw emotions like anger and rage”, tendency to “risk-taking and irresponsibility”, and personality changes such as “impulsivity” (Raine, 2014).

Other than the experiment of Raine et al. (1997), other researchers’ studies have also revealed other physical attributions of psychopathy and tendency towards violence (Gao et al., 2010; Ishikawa et al., 2001). A study on fear conditioning at age 3 and crime convictions at age 23 indicated children who later committed crimes showed no signs of fear conditioning at all, suggesting their lack of conscience (Gao et al., 2010). In the study of Ishikawa et al. (2001), unsuccessful psychopaths (unsuccessful psychopaths tend to behave more impulsively than successful psychopaths and are therefore more likely to be convicted), when placed under anticipation of stress and fear, show “blunted autonomic stress response”, minimal increases in heart rate and skin conductance; while successful psychopaths who are less likely to be captured demonstrate similar increases in heart rate and skin conductance as normal controls (Ishikawa et al., 2001). This illustrates that psychopaths do possess a difference to stress and fear conditioning behaviors as compared to normal controlled individuals. In the adoption study of Mednick et al. (1984), when offspring are separated from biological parents and become adopted, those with criminal biological parents commit crimes in the future at a higher rate than adoptees who have non-criminal biological parents (Mednick et al., 1984). This suggests the influences of genetics from criminal parents can be inheritable to their offsprings, generating a higher probability of crime convictions for their future progeny.

To identify and demarcate the definition of psychopathy, this study has taken into consideration two types of assessments, DSM-IV and PCL-R (American Psychiatric Association & American Psychiatric Association. Task Force on DSM-IV., 1994; Hare, n.d.). DSM-IV stands for the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (Fourth Edition) from the American Psychiatric Association; it serves to provide a set of guidelines and criteria for determination of psychiatric disorders, outlining essential characteristics of which (Stein et al., 2010). PCL-R is a Psychopathy Checklist developed by Canadian psychologist Robert Hare, using triangulation to assess psychopathy (Hare, n.d.). It takes information and data from police reports, case histories, and third parties, including families, friends, social workers, and teachers. Furthermore, due to its strictness of psychopathy evaluation, PCL-R usually produces a lower prevalence of psychopathy compared to other statistical tests. Namely, in a scientific review of literature by Sanz-Garcia et al. (2021), the researchers reviewed previous literature on the prevalence of psychopathy in the general population using meta analysis and PCL-R, receiving a result of 4.5% and 1.2%, respectively (Sanz-García et al., 2021). Moreover, it is vitally important to take into account that there remains sources of error in both types of psychopathy test, namely the subjectivity of psychopathy determination on the part of the tester; this means that while some behaviors are deemed corresponding to psychopathic characteristics by some testers, the same conditions are tolerated by others.

Data

ANOVA Results: Males in Violent Crime

The F ratio is the ratio of two mean square values. If the null hypothesis is true, you expect F to have a value close to 1.0 most of the time. A large F ratio means that the variation among group means is more than you'd expect to see by chance.

The results for males in violent crime (sex is held constant, age is variable) shows that younger males (age 12-24) commit significantly more violent crimes than the other age cohorts, with relatively large F ratio values.

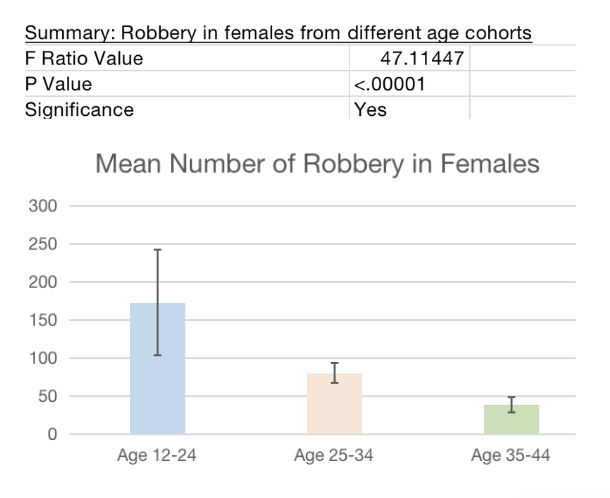

ANOVA Results: Females In Violent Crime

The results for females in violent crime (sex is held constant, age is variable) shows that younger females (age 12-24) do not necessarily commit significantly more violent crimes than the other age cohorts. (Small F ratio values) For homicide, younger females are not necessarily the age group that commits the most violent crimes. For attempted murder, the ANOVA result is not statistically significant.

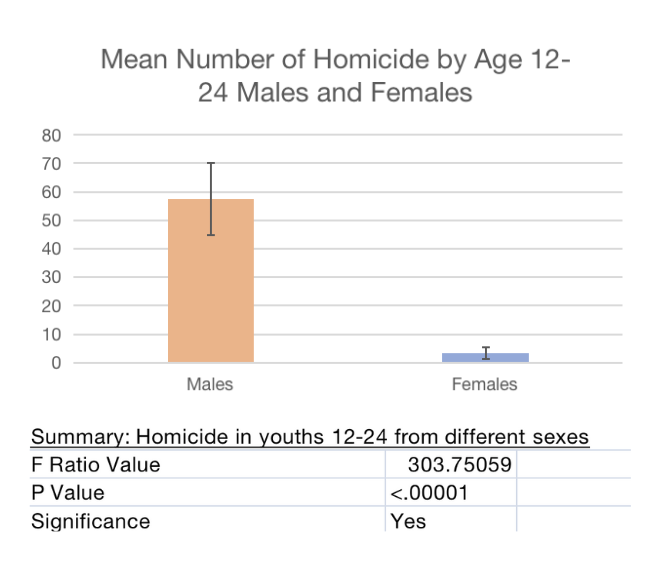

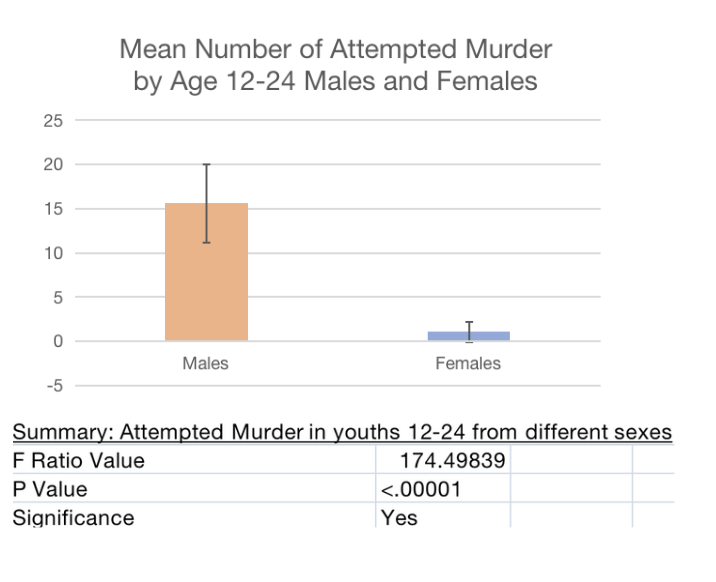

ANOVA Results: Males vs. Females

The results for males vs females in violent crime (sex is held variable, age is constant) shows that males (age 12-24) commit significantly more violent crimes than females (age 12-24), with large F ratio values.

Fisher’s Exact Test Results: Psychopaths vs. Non-psychopaths

The Fisher exact test statistic value is 0.0471. The result is significant at p < .05. Null hypothesis is rejected.

Psychopaths and non-psychopaths are not equally likely to commit violent recidivism.

Fisher’s Exact Test Results: Psychopaths vs. Federal Offenders <25

The Fisher exact test statistic value is 0.6567.

The result is not significant at p < .05. Null hypothesis cannot be rejected.

Federal offenders under the age of 25 and psychopaths can be equally likely to violently recidivate.

Fisher’s Exact Test Results: Psychopaths vs. Federal Offenders 30 - 35

The Fisher exact test statistic value is < 0.00001. The result is significant at p < .05. Null hypothesis is rejected.

Federal offenders between age 30 to 35 and psychopaths are not equally likely to violently recidivate.

Conclusion

- Males commit more violent crimes compared to females

- Young people (<25 year old) commit more violent crimes compared to older people (>25 years old)

- Psychopaths are more likely to persist in violent crimes compared to non-psychopaths

- Similarity between psychopathy and young age:

- young people (<30 years old) can be equally likely to persist in violent crimes compared to psychopaths

- Psychopathy could be an accurate predictor of violent crime and violent crime persistence (recidivism), and even crimes and offenses in general

- Biological reasons for crime

- neurobiological markers (underdevelopment of prefrontal cortex, for example) can be effective in identifying tendency towards crime

Citations

References

American Psychiatric Association, & American Psychiatric Association. Task Force on DSM-IV. (1994). Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders: DSM-IV. American Psychiatric Association. https://doi.org/10.1176/appi.books.9780890420614.dsm-iv

Arnsten, A. F. T. (2009). Stress signalling pathways that impair prefrontal cortex structure and function. Nature Reviews. Neuroscience, 10(6), 410–422. https://doi.org/10.1038/nrn2648

Crime statistics - crime severity index. (n.d.). Retrieved December 16, 2023, from https://open.canada.ca/data/en/dataset/f77dc929-5ff0-ddcc-30a0-c9773212484f

Definitions. (2010, June 29). https://www150.statcan.gc.ca/n1/pub/85-002-x/2010002/definitions-eng.htm

Falk, Ö., Wallinius, M., Lundström, S., Frisell, T., Anckarsäter, H., & Kerekes, N. (2014). The 1 % of the population accountable for 63 % of all violent crime convictions. Social Psychiatry and Psychiatric Epidemiology, 49(4), 559–571. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00127-013-0783-y

Female offenders in Canada, 2017. (n.d.). Retrieved December 16, 2023, from https://www150.statcan.gc.ca/n1/pub/85-002-x/2019001/article/00001-eng.htm

Forum on corrections research. (2007). https://www.csc-scc.gc.ca/research/forum/e012/e012l-eng.shtml

Gao, Y., Raine, A., Venables, P. H., Dawson, M. E., & Mednick, S. A. (2010). Association of poor childhood fear conditioning and adult crime. The American Journal of Psychiatry, 167(1), 56–60. https://doi.org/10.1176/appi.ajp.2009.09040499

Glenn, A. L., & Raine, A. (2014). Neurocriminology: implications for the punishment, prediction and prevention of criminal behaviour. Nature Reviews. Neuroscience, 15(1), 54–63. https://doi.org/10.1038/nrn3640

Government of Canada, & Canada, S. (2016, May 10). People accused of selected offences, by age group of accused and by offence type, 2014. https://www150.statcan.gc.ca/n1/daily-quotidien/160510/cg-c001-eng.htm

Government of Canada, & Canada, S. (2023). Crime severity index and weighted clearance rates, Canada, provinces, territories and Census Metropolitan Areas [dataset]. Government of Canada, Statistics Canada. https://www150.statcan.gc.ca/t1/tbl1/en/tv.action?pid=3510002601&pickMembers%5B0%5D=1.1&cubeTimeFrame.startYear=2015&cubeTimeFrame.endYear=2022&referencePeriods=20150101%2C20220101

Hare, R. D. (n.d.). Psychopathy Checklist—Revised. Psychological Assessment: A Journal of Consulting and Clinical PsychologyPsychological Assessment. https://doi.org/10.1037/t01167-000

Ishikawa, S. S., Raine, A., Lencz, T., Bihrle, S., & Lacasse, L. (2001). Autonomic stress reactivity and executive functions in successful and unsuccessful criminal psychopaths from the community. Journal of Abnormal Psychology, 110(3), 423–432. https://doi.org/10.1037//0021-843x.110.3.423

Measuring Crime in Canada: Introducing the Crime Severity Index and Improvements to the Uniform Crime Reporting Survey. (2009). Statistics Canada, Canadian Centre for Justice Statistics. https://play.google.com/store/books/details?id=aY0HkAEACAAJ

Mednick, S. A., Gabrielli, W. F., Jr, & Hutchings, B. (1984). Genetic influences in criminal convictions: evidence from an adoption cohort. Science, 224(4651), 891–894. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.6719119

Nakamura, J. (2021, February 25). State v. Yepez, 483 P.3d 576. https://casetext.com/case/state-v-yepez-4

Raine, A. (1993). The Psychopathology of Crime: Criminal Behavior as a Clinical Disorder. Gulf Professional Publishing. https://play.google.com/store/books/details?id=GPNgUrmaxkkC

Raine, A. (2014). The Anatomy of Violence: The Biological Roots of Crime. Knopf Doubleday Publishing Group. https://play.google.com/store/books/details?id=iiKODQAAQBAJ

Raine, A., Buchsbaum, M., & LaCasse, L. (1997). Brain abnormalities in murderers indicated by positron emission tomography. Biological Psychiatry, 42(6), 495–508. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0006-3223(96)00362-9

Renard, J., Rosen, L., Rushlow, W. J., & Laviolette, S. R. (2017). Role of the prefrontal cortex in addictive disorders. In The Cerebral Cortex in Neurodegenerative and Neuropsychiatric Disorders (pp. 289–309). Elsevier. https://doi.org/10.1016/b978-0-12-801942-9.00012-4

Sanz-García, A., Gesteira, C., Sanz, J., & García-Vera, M. P. (2021). Prevalence of Psychopathy in the General Adult Population: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Frontiers in Psychology, 12, 661044. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2021.661044

Stein, D. J., Phillips, K. A., Bolton, D., Fulford, K. W. M., Sadler, J. Z., & Kendler, K. S. (2010). What is a mental/psychiatric disorder? From DSM-IV to DSM-V. Psychological Medicine, 40(11), 1759–1765. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0033291709992261

Stoddard, J., Raine, A., Bihrle, S., & Buchsbaum, M. (1997). Prefrontal Dysfunction in Murderers Lacking Psychosocial Deficits. In A. Raine, P. A. Brennan, D. P. Farrington, & S. A. Mednick (Eds.), Biosocial Bases of Violence (pp. 301–304). Springer US. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-1-4757-4648-8_18

Government of Canada, & Canada, S. (2023a). Adult criminal courts, guilty cases by most

serious sentence [dataset]. Government of Canada, Statistics Canada. https://www150.statcan.gc.ca/t1/tbl1/en/tv.action?pid=3510003101&pickMembers%5B0%5D=1.1&pickMembers%5B1%5D=2.5&pickMembers%5B2%5D=3.2&pickMembers%5B3%5D=4.3&pickMembers%5B4%5D=5.1&cubeTimeFrame.startYear=2000+%2F+2001&cubeTimeFrame.endYear=2021+%2F+2022&referencePeriods=20000101%2C20210101

Government of Canada, & Canada, S. (2023c). Youth courts, number of cases and charges by

type of decision [dataset]. Government of Canada, Statistics Canada. https://www150.statcan.gc.ca/t1/tbl1/en/tv.action?pid=3510003801&pickMembers%5B0%5D=1.1&pickMembers%5B1%5D=2.5&pickMembers%5B2%5D=3.2&pickMembers%5B3%5D=4.3&pickMembers%5B4%5D=5.2&cubeTimeFrame.startYear=2000+%2F+2001&cubeTimeFrame.endYear=2021+%2F+2022&referencePeriods=20000101%2C20210101

Grann, M., Långström, N., Tengström, A., & Kullgren, G. (1999). Psychopathy (PCL-R) predicts

violent recidivism among criminal offenders with personality disorders in Sweden. Law and Human Behavior, 23(2), 205–217. https://doi.org/10.1023/a:1022372902241

Hart, S. D., Kropp, P. R., & Hare, R. D. (1988). Performance of male psychopaths following

conditional release from prison. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 56(2), 227–232. https://doi.org/10.1037//0022-006x.56.2.227

Hemphill, J. F., Strachan, C., & Hare, R. D. (n.d.). Psychopathy in female offenders. Manuscript

in Preparation.

Hodgins, S., Côté, G., & Ross, D. (n.d.). Predictive validity of the French version of Hare’s

Psychopathy Checklist. Canadian Psychology, Psychologie Canadienne.

Loucks, A. D. (2001). Predictors of criminal behavior and prison misconduct in serious female

offenders. https://citeseerx.ist.psu.edu/document?repid=rep1&type=pdf&doi=83f32dbe69a606a27802648b1a2199828a2e4762

Serin, R. C. (1996). Violent recidivism in criminal psychopaths. Law and Human Behavior,

20(2), 207–217. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF01499355

Serin, R. C., & Amos, N. L. (1995). The role of psychopathy in the assessment of dangerousness.

International Journal of Law and Psychiatry, 18(2), 231–238. https://doi.org/10.1016/0160-2527(95)00008-6

Stewart, L. A., Wilton, G., Baglole, S., & Miller, R. (2019). A comprehensive study of recidivism

rates among Canadian federal offenders. Correctional Service Canada, Service correctionnel Canada. https://www.csc-scc.gc.ca/research/005008-r426-en.shtml

Acknowledgement

Words certainly cannot express my sincere gratitude for my mentor, Dr Kirsten Johnson Kramar, for her invaluable feedbacks and expertise in the field of criminology. Furthermore, this project would not have been possible without the generous support from Dr Beatriz Garcia-Diaz, instructor of the Applied Science Project at Webber Academy. It is undoubtedly my utmost honor to have both of them supporting this project in my journey.