Pills for Panic: Comparison of Benzodiazepines and SSRIs for the Treatment of Panic Disorder

Grade 8

Presentation

Problem

Problem

SSRIs and benzodiazepines have been battling to be the best pharmacological treatment for panic disorder for many years. Unnecessary and untrue bias was expressed towards both treatments with little evidence to support the claims. By conducting this review it is hoped that an end is put to this debate and gain the most comprehensive view on this subject.

Research Question

After the gathering of background information was complete, the following research question was developed:

What are the comparative results of benzodiazepines versus selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs) in the treatment of panic disorder with or without agoraphobia in adults when considering dropout rate, rate of remission, and adverse effects?

Objective

The objective of this review is to compare the effects of SSRIs and benzodiazepines on adults with panic disorder, particularly:

- to determine which of the two is more effective in treating panic disorder with or without agoraphobia using the rate of remission as a scale;

- to measure the total amount of dropouts in both groups due to any reason and use it as a proxy measure of acceptability; and

- to determine and compare the amount of adverse effects for SSRIs and benzodiazepines.

Method

Eligibility Criteria

Types of Studies

Studies such as double‐blind randomised controlled trials (RCTs), meta-analysis, and systematic reviews written and conducted in the last 15 years (as of December 2024) addressing at least one of the following topics of interest: dropout rate, rate of remission, and measures of adverse effects. The studies had to directly compare benzodiazepines and SSRIs for the treatment of panic disorder and had to have 25 or more participants. Any studies that did not have free or easily accessible full text versions or were not written in English were excluded. The studies in this review meet all of the listed criteria.

Participants

Participants had to be officially diagnosed with panic disorder, over 18 years of age, and have no serious physical or psychiatric comorbidities. Unfortunately, due to the lack of studies and its common presence in patients with panic disorder, studies with patients with comorbid agoraphobia were included in this review.

Search Strategy

A search of the following four electronic databases was conducted: Science Direct, PubMed, PsycNet, and the Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews (CDSR). A filter was set to exclude studies published more than 15 years before the day that the search was conducted (1 December, 2024). The keywords “panic disorder” AND “benzodiazepine” AND “SSRI” were used, however the search was altered and other keywords were used in place. “Benzodiazepines” was used in place of “benzodiazepine” and “SSRIs” in place of “SSRI”. The specific medication names were also replaced by “pharmacological” AND “treatments” or just “treatment” to obtain broader results. The first search terms were used the most. The search was conducted by one independent researcher and PRISMA guidelines were used.

Synthesis Methods

After the search was completed, data that reported outcomes of interest were extracted. This was done manually by one independent researcher. Of the three included studies only Chawla et al. (2022) clearly reported all measured outcomes, while the others presented results differently, requiring the data to be converted. While Bighelli et al. (2016) reported on all three outcomes of interest, the comparison was between SSRIs and benzodiazepines rather than benzodiazepines and SSRIs, which was the format the rest of the studies presented their outcomes. For that reason, all three of the statistical summaries (risk ratios and confidence intervals) that were being used in this review from Bighelli et al. (2016) had to be “flipped”. This was done according to the formula which states that the inverted risk ratio can be found by dividing one by the risk ratio; in other words the inverted risk ratio is the reciprocal of the original risk ratio. Same goes for the upper limit (UL) and lower limit (LL) of the confidence interval. The flipped upper limit is the reciprocal of the lower limit and vice versa.

(Figure 1)

(Figure 2)

Additionally, while Bighelli et al. (2016) reported on remission and adverse effects, they presented two out of the three outcomes in a negative way (failure to remit and which treatment has a higher number of adverse effects) despite the preferred reporting method of this data for this review being a positive presentation (rate of remission and which treatment has a lower number of adverse effects). To convert the negative presentation to a positive, the same formula as previously used to flip the comparisons was used. This resulted in the twice adjusted risk ratios and confidence intervals to be the same as their respective originals.

Finally, Guaiana et al. (2023) reported their results in the Baysian method rather than the frequentist like all other studies in this review (uses credible interval instead of confidence interval, etc.). This made the creation of graphs difficult as there is no direct conversion between them. It was decided to include a separate section for results from Guaiana et al. (2023) into the graphs or presented it in a narrative format as seen below in Table 3. The original and adjusted results can be seen in Tables 1 and 2 respectively.

(Table 1) Raw data

(Table 2) Adjusted Data. Guaiana et al. (2023) reported a Bayesian risk ratio of 0.62 and credible intervals (Crl) of 0.44 to 0.83.

Data Management

Dichotomous Data

All data gathered was found to be dichotomous (binary), using risk ratios (RR) and with corresponding 95% confidence intervals (CIs). It was decided that it was not to convert to odds ratio (OR) as they are generally considered more difficult to understand than risk ratios (Grimes & Schulz, 2008). For these reasons it was not necessary to estimate risk ratios or any other type of statistical summaries before conducting the meta analysis.

Missing and Insufficient Data

Fortunately, no missing data was identified for the observed outcomes, however this presented itself with other challenges. Within the two syntheses included in this meta analysis, there were only three smaller studies (all randomised controlled trials), one in Bighelli et al. (2016) and two in Chawla et al. (2022). This created a number of problems, as it meant that while the pooled effect estimates would be more accurate, it still wouldn't be able to accurately portray the situation outside of the conducted clinical trials.

Data Synthesis

After the initial completion of the systematic review, it was decided that a meta analysis was able to be conducted. However, it is worth noting that Guaiana et al. (2023) was excluded from the meta-analysis as it is a study done in Bayesian statistics, rather than the preferred frequentist. A standard inverse variance meta-analysis was conducted, using a fixed-effects model for the first two observed outcomes (dropout rate and remission) and a random-effects model for the last (adverse effects). This was done because the results from both studies of the first two outcomes were extremely similar, alluding to a similar true effect and low heterogeneity. In the final outcome of adverse effects a large difference between the reported results was observed. As previously mentioned, it was decided to use a random-effects model due to the fact that it better accounts for the variation that was present, creating a more accurate representation of the effect of the intervention.

It was determined that the statistical software R would be the best tool to conduct this meta-analysis. The software uses the same-named programming language, however due to its rarity and scarce applications elsewhere, we were not familiar with this language. For this reason it was decided to use a generative artificial intelligence to create code that would do the desired function. However, it is important to note that the created code was not perfect and contained example data only. It had to be manually adjusted and the retrieved results from included studies were also entered by hand. Additionally, the generative artificial intelligence did not conduct the meta-analysis nor did it receive or interpret the results. The code was exported to the previously mentioned statistical software R where the analysis was conducted and data was extracted for interpretation. This was done manually by one independent researcher.

Heterogeneity

As per the Cochrane Handbook of Systematic Reviews of interventions, heterogeneity is to be qualified using I2 (based on Cochran’s Q) and Chi2, along with its p-value. Heterogeneity was interpreted as the following:

- 0% to 40%: might not be important;

- 30% to 60%: may represent moderate heterogeneity;

- 50% to 90%: may represent substantial heterogeneity;

- 75% to 100%: considerable heterogeneity.

The conventional threshold of ≤0.05 for the p-value of Chi2 was used to indicate statistically significant results. Unfortunately, due to the low number of studies included in the meta-analysis, meta regression and subgroup analyses were not able to be conducted. The results would have been unreliable as there would have been more parameters that accounted for the heterogeneity than data points present.

Research

Background Research

Panic Disorder

Panic disorder (PD) is an anxiety disorder characterized by untriggered and unexpected panic attacks and a persistent fear of the attacks occurring again (Panic Attacks and Panic Disorder - Symptoms and Causes, n.d.). According to the DSM-5, panic disorder without agoraphobia has a lifetime prevalence of about 3% in the United States. Most often this disorder is diagnosed in the earlier stages of a person’s life and if left untreated can negatively impact quality of life, leading to many future problems such as problems with socialization or developing of other disorders (Panic Disorder: When Fear Overwhelms, n.d.).

Causes of Panic Disorder

The prime symptom of PD, panic attacks, are usually not triggered in any way, and even now the exact causes are yet to be discovered (Panic Attacks and Panic Disorder - Symptoms and Causes, n.d.). It is important to note that it is possible to experience a panic attack due to a phobia or intense anxiety but in the case of panic disorder, the attacks are always seemingly untriggered. It is popularly believed that anxiety and mood disorders are caused by serotonin deficiencies, and while that is true, it is not the only cause (Panic Attacks &Amp; Panic Disorder, 2024). For panic disorder, there are several known risk factors that can make a person more likely to develop this disorder. First, researchers have found a trend showing that panic disorder has a major genetic factor. If a close relative has PD a person is about 40% more likely to develop this disorder. PD is also often comorbid with other mental disorders such as major depressive disorder. Finally, traumatic experiences have been found to contribute to the likelihood of panic disorder developing. Because of the mentioned risk factors it is likely that panic disorder has epigenetic components. It is possible that a problem with the functioning of the amygdala or with production of neurotransmitters is the cause of the condition itself, but it is still being investigated by researchers (Yoon et al., 2016).

Symptoms of Panic Attacks

Oftentimes patients experiencing an attack will confuse it with another health condition such as a heart attack due to the many similar physical symptoms and its unexpectedness. Those include the following:

- Rapid heartbeat

- Sweating

- Chills

- Shaking

- Difficulty breathing

- Fatigue or vertigo

- Tingling or numbness in nerve endings

- Chest pain

- Abdominal pain or nausea

(Panic Disorder: When Fear Overwhelms, n.d.)

A panic attack is described as a sudden and extremely strong wave of fear and a truly terrifying experience (Panic Attacks and Panic Disorder - Symptoms and Causes, n.d.). The panic will peak about ten minutes after the symptoms first begin and usually end soon after (Panic Attacks &Amp; Panic Disorder, 2024). During that time the person will feel as if they have lost all control or, in some cases, that they are dying (Panic Disorder: When Fear Overwhelms, n.d.).

Medication For Panic Disorder

While panic disorder can be treated with many different types of medication, SSRIs and benzodiazepines are the most common. Despite usually being an antidepressant used to treat depression and other mood disorders, SSRIs (selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors), can also be used for PD. Benzodiazepines (BZDs, benzos) are a commonly used type of anti-anxiety medications. Although they are able to mute the effects of panic disorder in a short amount of time, they are also quite easy to build a tolerance to, which can result in addiction and overdose. Usually the optimal medication is individual to the person. Not all medications for this type of disorder work the same for all people, and sometimes patients will need to try several different treatments to find the best one. If it is found that a medication is not working, the doctor may recommend a different medication or combination of treatments, such as psychotherapy and medication, to find an effective one. It is also important to note that most of the time significant improvements in the patient's mental health that will likely last will only be seen after a couple of weeks (Panic Attacks and Panic Disorder - Symptoms and Causes, n.d.).

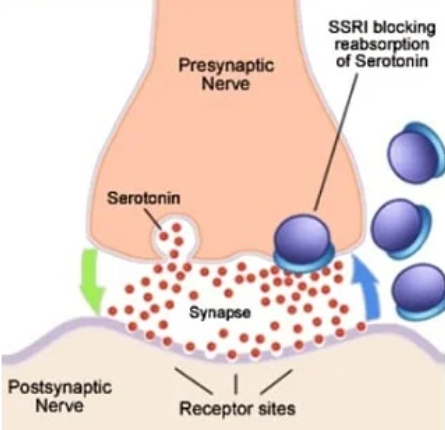

How the Intervention Works

It is believed that the deficiency of serotonin (5-hydroxytryptamine/5HT) can partially be the cause of panic disorder. During neurotransmission, serotonin is first released from the presynaptic axon terminal into the synapses (synaptic gap/synaptic cleft). When the serotonin tries to be reuptaken into the presynaptic nerve, the SSRI inhibits that process, forcing the neurotransmitter to stay in the synapses. This means that serotonin will continue to be released into the synapses but it will no longer be able to be removed from there via reuptake, meaning that there chances of the neurotransmitter contacting and binding to its respective receptor on the postsynaptic nerve and stimulating is much increased (Chu & Wadhwa, n.d.). Thus, the brain is forced to use the serotonin it already has more efficiently, resulting in positive effects on mood and emotion (MSc, 2023).

MSc, O. G. (2023, July 20). Types of antidepressants and how they work. Simply Psychology. https://www.simplypsychology.org/major-classes-of-antidepressants.htm

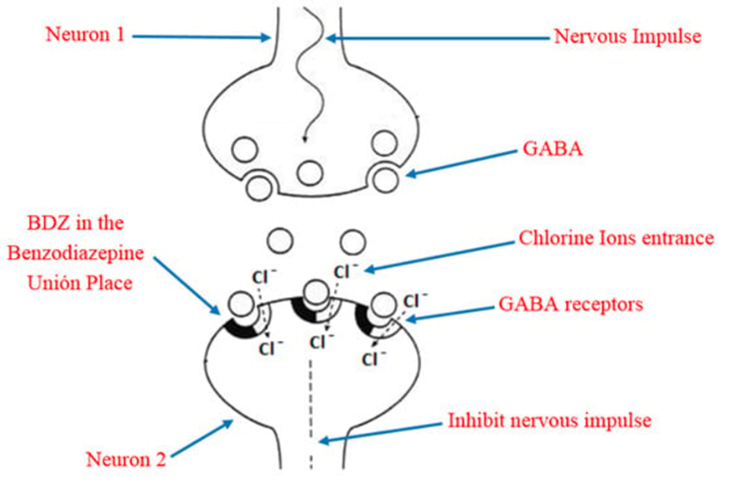

Benzodiazepines work by interacting with the GABAA receptor and enhancing the properties of the gamma-aminobutyric acid, or GABA, neurotransmitter, which results in lowered anxiety and light sedation. GABA is the main inhibitory neurotransmitter in the CNS, which is thought to be responsible for reducing feelings of stress and anxiety. After GABA is released from the presynaptic nerve, it travels across the synapses and binds to the GABAA receptor (which is a channel-forming protein). The receptor then temporarily opens the channel to allow negatively charged molecules called chloride ions to go inside of the postsynaptic nerve (Benzodiazepines: How Do They Work?, n.d.). This lowers the cell's excitability, meaning that its ability to respond to stimuli through electrical impulses is slowed or decreased (Neuronal Excitability | the Human Brain, n.d.). BZDs attach themselves to the benzodiazepine binding site on the GABAA receptor and stimulate it for longer, allowing more chloride ions to enter the cell. The result is the more than naturally possible depression or slowing of nerve impulses, meaning that nerve responses and general reaction time are severely decreased, thus the name central nervous system depressants (Benzodiazepines: How Do They Work?, n.d.).

Sanabria, E., Cuenca, R. E., Esteso, M. Á., & Maldonado, M. (2021). Benzodiazepines: Their Use either as Essential Medicines or as Toxics Substances. Toxics, 9(2), 25. https://doi.org/10.3390/toxics9020025

Potential Side Effects of SSRIs

Unlike other commonly used antidepressants such as TCAs and MAOIs, SSRIs have a considerably smaller amount of side effects and are considered a lot more tolerable. As the name suggests, SSRIs are selective, meaning that unlike other antidepressants, they rarely affect neurotransmitters besides serotonin, resulting in smaller chances of more serious side effects such as cognitive problems and urinary retention. The most concerning potential side effect of this medication is the increased risk of suicidal thoughts. This was primarily observed in teens and young adults under the age of 25. While this risk should be considered when prescribing medication, the mental condition could also be causing such symptoms. One of the more serious physical side effects is the risk of prolonging QT intervals (Chu & Wadhwa, n.d.-a). QT intervals is the time between the Q and T waves during a heartbeat cycle. The interval shows the electrical activity in the heart’s lower chambers. When the electrical signals that tell the heart to beat are not normal, it is called arrhythmia, or irregular heartbeat (Long QT Syndrome | NHLBI, NIH, 2022). The use of SSRIs can sometimes lead to extreme or even fatal cases of this. Since SSRIs increase the amount of serotonin in the synaptic cleft, thus stimulating the serotonin receptors a lot, serotonin syndrome can be an uncommon but dangerous risk. Serotonin syndrome is a serious bodily reaction to increased levels of serotonin that can cause many dangerous and uncomfortable physical symptoms. Finally, some of the most commonly reported side effects of SSRIs include but are not limited to sexual dysfunction, sleep disturbances, weight changes, anxiety, dizziness, xerostomia, headache, and gastrointestinal distress (Chu & Wadhwa, n.d.-a).

Potential Side Effects of Benzodiazepines

Despite being great at rapidly relieving the symptoms of panic disorder and generally being safe to use in the short-term, benzodiazepines can have some very serious physical and cognitive side effects. Some of the more common short term side effects include but are not limited to fatigue, muscle function impairment, visual disturbances such as hallucinations, cardiovascular irregularities such as an irregular heartbeat, confusion, digestive problems, loss of coordination and/or vertigo, and slowed reaction time. Because of the last named effect, patients under the effects of benzodiazepines usually aren’t allowed to drive, as that would be considered impaired driving (Benzodiazepines: How Do They Work?, n.d.). Depending on the type of benzodiazepine and its dosage, patients may experience anterograde amnesia which is when new memories temporarily cannot be formed (Mejo S. L.,1992).

BZD are easy to build a tolerance to and if used in the long-term can cause physical dependence and addiction. Because of this they are very widely misused and even abused, which most often either leads to overdose or to withdrawal symptoms when they are taken away. Patients taking benzodiazepines are not allowed to drink alcohol or take similar substances as they can increase the effects of the drug and can lead to an overdose.Respiratory depression which may result in respiratory arrest and/or a coma are the usual effects of benzodiazepine overdose. This is when breathing completely stops, and it can be fatal if medical help is not provided immediately. Flumazenil, a benzodiazepine antagonist, can be used to treat overdoses, as it can fully or partially reverse the sedative effects of the drug. When benzodiazepines and other substances such as opioids mix and result in an overdose, naloxone is used. While it can help restore breathing, it will not reverse the sedation caused by the benzo so the patient will likely remain in the coma for several more hours. Because of all these potential side effects the distribution of benzodiazepines is heavily controlled (Benzodiazepines, n.d.) (Benzodiazepines: How Do They Work?, n.d.).

SSRIs that Treat Panic Disorder

Currently, there are only three SSRIs approved by the FDA (Food and Drug Administration) for the treatment of panic disorder (Panic Attacks and Panic Disorder - Symptoms and Causes, n.d.). They are as follows:

- Fluoxetine, sold under the brand name Prozac, Average adult dosage: 20 to 60 mg/d.

- Paroxetine, sold under two brand names; Paxil and Pexeva, Average adult dosage: 20 to 40 mg/d.

- and Sertraline, sold as Zoloft, Average adult dosage: 100 to 200 mg/d.

Named medications are usually taken in the form of a pill or tablet that are taken at least once a day depending on the severity of the disorder (Panic Attacks and Panic Disorder - Symptoms and Causes, n.d.). Other SSRIs may be used to treat panic disorder as well, but that is considered off-label usage. This, by definition from the FDA, means that the given drug was not approved by them to treat said disorder, was given in a different form than usual, or the dosage is different. This may happen because there is no specific medication for the disorder, but this is not the case for panic disorder. While uncommon, a health care provider might prescribe a drug off-label because all of the officially approved medications had no positive effect or effect in general (Zamorski & Albucher, 2002).

Benzodiazepines that Treat Panic Disorder

As of 2024, two benzodiazepines can be prescribed for panic disorder (Panic Attacks and Panic Disorder - Symptoms and Causes, n.d.).They are as follows:

- Alprazolam (Xanax), Average adult dosage: 1 - 4 mg/d.

- and Clonazepam (Klonopin), Average adult dosage: 1mg/d.

They are the two FDA approved benzodiazepines for the treatment of panic disorder. While they are generally safe to use in the short-term, they’re also fast-acting and quite addicting, so their distribution and dosages are heavily controlled. This type of medicine is typically not prescribed to people who have records of substance abuse and/or addiction. While BZDs are great at rapidly relieving the severe symptoms of panic disorder, the effect only lasts for a couple hours after which the symptoms may return even stronger (Panic Attacks and Panic Disorder - Symptoms and Causes, n.d.). Just like with SSRIs, other BZDs can be prescribed to treat panic disorder, but it will be off-label usage (Bounds & Patel, n.d.).

Agoraphobia

Agoraphobia is an anxiety disorder that most commonly occurs when panic disorder is also present. It is characterized by a fear of becoming overwhelmed or not being able to escape a place or situation. For this reason, people with this disorder avoid places or situations that are very crowded, open, or enclosed. In severe cases, the patient may not leave their houses altogether (Agoraphobia - Symptoms and Causes, n.d.) (Agoraphobia, 2025). Unfortunately, despite initially not wanting to include any studies where patients had comorbid conditions, but due to its prevailing presence, I was forced to include studies where patients were with or without agoraphobia. Comorbidity in panic disorder can result in higher levels of anxiety, more depressive symptoms, and more suicidal thoughts. All of these factors can affect treatment outcomes, which is why it is important to consider comorbidities when creating a treatment plan (Lecrubier Y., 1998).

Experts' Opinion

Dr. Chad Bousman, PhD, MPH

- While there is no clear cause for panic disorder genetic and environmental risk factors have been identified. Is it possible that this disorder is caused by epigenetics? If so, can gene therapy be an option for patients in the future? If it is not possible that the disorder is caused by epigenetics why is that?

Yes, it is possible that panic disorder has an epigenetic component. Gene therapy, though not yet feasible for panic disorder, holds potential as our understanding of the epigenetic and genetic underpinnings of psychiatric disorders grows. However, the complexity of panic disorder, means that any future treatments will likely need to address multiple biological and psychological systems, not just genetic or epigenetic factors alone.

- Panic attacks in panic disorder are known to be seemingly untriggered, but abnormalities relating to serotonin (5-HT) were linked to them. Is the problem with the production of serotonin (not enough serotonin being produced or the brain “doesn’t know/can’t” produce it, kind of like with diabetes, explaining why SSRIs don’t work for everyone) or is it with the serotonin receptor (does not signal properly or doesn’t properly bind with serotonin)? Is it possible that the seemingly untriggered panic attacks (in panic disorder) are like the body’s reaction to a deficiency from serotonin, almost like a withdrawal reaction?

Serotonin dysregulation in panic disorder likely involves a combination of production, release, and receptor function abnormalities. While it’s not entirely accurate to liken panic attacks to a serotonin “withdrawal", the analogy captures the idea that serotonin dysfunction might mimic a deficiency state, leading to over-activation of the brain's panic pathways. Addressing this complexity may require personalized treatments targeting both serotonin and other involved systems, such as the GABAergic and noradrenergic pathways.

- Do you feel like enough research was done to explain the effects of psychotropic medications on the human central nervous system? What are the limitations of such research?

In short, no. While considerable progress has been made, the understanding of psychotropic medications is far from complete. Limitations in research methods, the complexity of the CNS, and individual variability make it difficult to fully explain how these drugs work or why they fall short for some patients. Addressing these gaps requires a multidisciplinary approach, combining advanced neuroscience, genetics, and patient-centered studies to develop safer and more effective treatments.

- Are SSRIs and benzodiazepines a “mask” and just temporarily “hide” the symptoms (high rate of relapse, even if it takes several years) or can they make substantial long-term changes (lower rate of relapse)? If it is the latter, how does it happen since the effects of the medication eventually wear off? Is the patient simply calmer allowing more serotonin to be produced?

Benzodiazepines generally “mask" symptoms without inducing long-term changes and are best used as short-term or adjunctive treatments. SSRIs have the potential to create lasting changes in brain function and structure, particularly when combined with psychotherapy or behavioral interventions. However, their effects vary, and relapse is common if underlying vulnerabilities are not addressed. The key to long-term success often lies in a combination of medication, therapy, and lifestyle changes, addressing both the biological and psychological aspects of the disorder.

- SSRIs are typically considered the first line of medication for panic disorder rather than benzodiazepines because of the latter’s higher risk of adverse effects and addition, but have you seen any difference in the outcome (rate of remission)?

Studies suggest that remission rates for SSRIs and benzodiazepines are similar in the short term, but SSRIs are more effective in maintaining remission over time. SSRIs are preferred for panic disorder because they offer better long-term outcomes and fewer risks of adverse effects. Benzodiazepines are best reserved for short-term use or adjunctive therapy during acute phases. Combining SSRIs with psychotherapy is the most, effective approach to achieving and maintaining remission in panic disorder.

Dr. Cynthia Baxter, MD, FRCPC, DABPN

- As a psychiatrist, how do you develop treatment plans? What are some of the things you consider?

The first thing that we should do, obviously, is talk to the patient and get a full history. Not just what symptoms they have but their background, where they come from, their medical history, and a very comprehensive analysis of them and their behavouir. Afterward, you may collect collateral information, and that means collecting old records. If they’ve been seeing someplace else, or depending on the scenario, talking to family members. It also it may be important to do certain laboratory tests to rule other possiblities. For example, thyroid disorders. They can replicate the symptoms of anxiety disorders.

Generally, when we decide on treatment, we follow clinical practice guidelines. Most physicians would be expected to follow the guidelines for the condition that you’re treating as well as considering the risks and benefits of each of the treatment options. You would consider that patient preference and avaliblility is a real issue as many things would be ideal for a patient to have, but that may not be possible. Taking into account other medical conditions is also very important.

- What is usually your first recommended treatment after a panic disorder diagnosis? Would it be CBT (cognitive-behavioural therapy), psychotherapy (talk therapy), or an intervention with medication?

It would be CBT for sure (cognitive behavioral therapy), thatwould absolutely be first line. The trouble is that many people don’t have access to therapy. Take Calgary for example. An appointment at Alberta Health Services clinics, which people can access for free, can be very difficult to arrange, and all you’ve got is a panic disorder diagnosis. Private therapy, on the other hand, is incredibly expensive. I think the going rate for psychology these days is around 230 dollars an hour. For us to consider intervention with medicaion the symptoms would have to be pretty severe. However, both the doctor and the patient need to be realistic that it’s probably not going to solve the issue, it just might make it a bit better.

- SSRIs are typically considered the first line of medication for panic disorder rather than benzodiazepines because of the latter’s higher risk of adverse effects and addition, but have you seen any difference in the outcome (rate of remission)?

Clinically, that’s not really a question anymore. The safety of benzodiazepines has been shown to really be problematic. It used to be given out a lot because it dampened down anxiety quite quickly and quite effectively, but it has many issues. There are lots and lots of potential risks, it’s highly addictive, so nowadays benzodiazepines are seen as relatively unsafe. So in my practice, I actually don’t prescribe them at all. The only scenario where you’ll get me to prescribe a benzodiazepine is after a highly tramatic event. They certainly are not safe long term but some physicians will give them for a couple of weeks until the SSRI kicks in. Your question, “have you seen any difference in the outcome of rate to remission?” Well, we just wouldn’t see it because not many people are being treated with benzodiapines anymore.

- Do you feel like enough research was done to explain the effects of psychotropic medications on the human central nervous system? What are the limitations of such research?

Of course not, because how could we? The brain is an incredibly complicated organ that we’re really only starting to understand. There’s lots of hypotheses and theories about what causes depression, anxiety, addiction, and even psychosis. So, lots of theories, but at the end of the day, we actually still don’t really know. We’ll really have to do more effective research, because if we only know what we know right now, we only have limited ways of assessing the brain. At this point we don’t really have the knowledge of we’re supposed to do in order to investigate the brain. So, people do their best, and we go by theories, but it would be a mistake to think that we really understand the brain at this moment.

- How often do you find that you have to prescribe an off-label medication for panic disorder? What is the main reason?

For a panic attacks, it would be pretty common to prescribe something like a beta blocker. Propranolol, for example. It would be common to give that kind of medication to somebody who’s having a panic attack because it literally blocks the adrenaline from having its effects. That would be a common one that we would use off label for panic attacks because it’s pretty safe.

- While there is no clear cause for panic disorder, genetic and environmental risk factors have been identified. Is it possible that this disorder is caused by epigenetics? If so, can gene therapy be an option for patients in the future?

It’s certainly an interesting advancement for lots of different disorders, being able to modify how DNA is expressed without actually changing it. But what we know about mental health and psychiatric disorders is that they are extremely complicated and that they are very rarely casues by only one factor like epigenetics. As for gene therapy, while everyone is quite excited and hopeful there is no guarantee that everyone will benefit from it or that it will be particularly effective at all.

Dr. Sudhakar Sivapalan, MD, FRCPC, MSc

- What is usually your first recommended treatment after a panic disorder diagnosis? Would it be CBT (cognitive-behavioural therapy), psychotherapy (talk therapy), or an intervention with medication?

Depending on age and severity of presentation, most clinicians will consider CBT and psychotherapy first. However, sometimes it is important to gain some control over the intensity of the symptoms and so medications may be introduced early on. In a younger population, the guidelines will suggest medications as second line. One of the challenges in many jurisdictions is getting access to good quality CBT or psychotherapy in a timely fashion.

- Would prescribing benzodiazepines still be clinically relevant for panic disorder or other anxiety disorders, considering some of their risks?

Benzodiazepines can still have a role in the treatment of panic disorder when used appropriately. This may mean have a small dose available to be taken at the onset of the panic episode. They can be fairly effective when used this way, but requires monitoring. The goal is to take the edge off the episode, but to not become reliant on taking a benzodiazepine as the only management tool. The role of benzodiazepines should primarily be limited to the early phase of treatment while using other medications such as SSRIs and/or psychotherapy/CBT. Benzodiazepines are generally not recommended as a first line treatment for any anxiety disorders.

- SSRIs are typically considered the first line of medication for panic disorder rather than benzodiazepines because of the latter’s higher risk of adverse effects and addition, but have you seen any difference in the outcome (rate of remission)?

In terms of directly treating the anxiety, benzodiazepines are generally considered to have a greater effect size than SSRIs. This has also been my clinical observation, although I do not have any specific statistics. However, as you indicate, the safety concerns, especially with longer term use often outweigh the benefits and so SSRIs/SNRIs are considered first line.

- At the end of treatment, are people generally more pleased with the outcomes from SSRIs or benzodiazepines? Are there any trends or is it individual to every patient?

I’m not sure I have seen a huge difference in terms of patient preference with outcomes. Benzodiazepines, even in the short terms can be cognitively blunting, overly sedating, withdrawal reactions, dizziness and contribute to respiratory problems. Many people find it difficult to tolerate those side effects. SSRIs/SNRIs on the other hand can lead to GI upset, headaches, sleep disruption, sexual side effects, and weight changes. The severity of side effects can vary with the individual, the dose, and can be dependent on what other medications the person may be taking.

- Do you feel like enough research was done to explain the effects of psychotropic medications on the human central nervous system? What are the limitations of such research?

There are been a fair amount of research, however, more is needed. The biggest limitations are often around ethical considerations, available technology (i.e. type of neuroimaging), and time. This takes significant funding to do, and the amount of money spent on Mental Health Research is often limited compared to other diseases/illnesses.

- How often do you find that you have to prescribe an off-label medication for panic disorder? What is the main reason?

I will often use other medications off label instead of starting someone on a benzodiazepine. One of the reasons it is considered off-label use is that the manufacturer of the medication did not apply for the indication, but the understanding of pharmacokinetics suggest its benefit.

- While there is no clear cause for panic disorder, genetic and environmental risk factors have been identified. Is it possible that this disorder is caused by epigenetics? If so, can gene therapy be an option for patients in the future?

Definitely, genetics appears to play a role. In the future, gene therapy may be an option, but given the theory that there are likely hundreds of genes involved, it would be very difficult to design an appropriate therapy with current technologies.

- Overall, do you find that you prescribe more SSRIs or benzodiazepines? Is there a particular reason for that?

Overall, I suspect that I prescribed more SSRIs/SNRis than I do benzodiazepines. Usually after the benefits and side effects of the options, both short term and long terms, most of my patients will choose to try the SSRI first anyway. If someone is referred to me already taking benzodiazepines, I will not automatically discontinue them, but it becomes part of the longer discussion around treatment goals and options. I do have a few patients whose anxiety is primarily managed with benzodiazepines that they have been on for some time and would find it quite difficult to stop.

Results

Screening and Selection Process

A total of 1459 studies were identified and exported to Endnote Basic. Using the program’s duplicate remover 180 duplicates were removed. The remaining 1279 studies’ titles and abstracts were screened and 1260 were excluded. The remaining 19 were to be retrieved for full-text screening but unfortunately 8 weren’t because their full-text versions were not accessible. Finally, 11 studies were assessed for eligibility with 8 of them being excluded. Six of them because they did not contain a direct and clear comparison between SSRIs and benzodiazepines, one because it did not focus on panic disorder, and the last one was excluded because it was a RCT within a meta analysis that was included in this review. Studies deemed similar by the databases were also screened. Therefore, this review includes two meta-analyses and one systematic review (Figure 1). The screening and selection process was conducted by one independent researcher.

(Figure 5) Flow diagram

Characteristics of Included Studies

From the three included studies a total of 766 participants have been identified. Unfortunately, Guaiana et al. (2023) did not specify how many participants were in each group, meaning that exact number of patients being treated with SSRIs or benzodiazepines is unknown. Additionally, the two meta-analyses (Guaiana et al. (2023) and Chawla et al. (2022)) did not specify the age of participants, besides quote “All participants were over the age of 18” or “the participants were adult”. All three reviews had an unspecified number of participants with agoraphobia. Other characteristics are shown in Table 3.

(Tabel 3) Characteristics of included studies

Effects of Intervention

The only outcome assessed and reported by all three studies was dropout rate of benzodiazepines compared to SSRIs. All reported results were similar and statistically significant, with little variation and showing a clear trend. Bighelli et al. (2016) reported a risk ratio of 0.58 with a 95% confidence interval of 0.35 to 0.97, indicating statistical significance. The two meta-analyses (Chawla et al. and Guaiana et al.) showed similar results. A risk ratio of 0.51 and a 95% confidence interval of 0.38 to 0.67 were reported by Chawla et al. (2022). Guaiana et al. (2023), being a study done in Bayesian statistics, cannot have its results interpreted in the exact same way as the other two studies. Nonetheless, the study showed conclusive results of RR 0.62, 95% Crl (credible interval) 0.44 to 0.83. Overall, all studies reported, with statistical significance, that benzodiazepines have a significantly lower dropout rate than SSRIs.

(Table 4) Dropout rate, benzodiazepines versus SSRIs

Unfortunately, the remission outcome was only measured by two studies, Bighelli et al. (2016) and Chawla et al. (2022). The studies were once again in agreement with each other, the reported results however, cannot be considered statistically significant as the lower limit crossed one in both cases. Bighelli et al. (2016) observed a slightly higher chance of remission in the SSRI group compared to the benzodiazepine group, presenting a risk ratio of 1.12 and a 95% confidence interval of 0.79 to 1.59. Chawla et al. (2022) showed a risk ratio slightly lower than the systematic review: RR 1.07, 95% CI 0.96 to 1.19. While the results were consistent, with SSRI having a higher remission rate, the data was not statistically significant.

(Table 5) Remission rate, benzodiazepines versus SSRIs

Finally, adverse effects were measured in the same studies that reported on the previous outcome, Bighelli et al. (2016) and Chawla et al. (2022). The results here differed significantly. Bighelli et al. (2016) reported that benzodiazepines and SSRIs have almost the same amount of adverse effects (RR 1.03 95% CI 0.92 to 1.15) with no statistical significance. On the other hand, Chawla et al. (2022) showed that SSRIs have a significantly lower amount of adverse effects compared to benzodiazepines with a risk ratio of 1.47 and a 95% confidence interval of 1.18 to 1.84. While it was observed that SSRIs have less adverse effects, there is quite the large difference in the reported statistics, making it more difficult to make accurate conclusions.

(Table 6) Adverse effects, benzodiazepines versus SSRIs

Pooled Effects of Intervention

In the outcome of dropout rate, due to the smaller range between the lower and upper confidence intervals, Chawla et al. (2022) had a greater weight in this outcome. This resulted in the pooled risk ratio estimate of a 0.53 risk ratio and a 95% confidence interval from 0.41 to 0.67 to be slightly closer to that of Chawla et al. (2022)’s original estimate, rather than Bighelli et al. (2016)’s. No heterogeneity or variance was found, and the Z-test’s p-value was < 0.0001, significantly lower than the established threshold of less or equal to 0.05 for statistical significance. This indicates that benzodiazepines have a significantly lower dropout rate than SSRIs, with statistical significance. Guaiana et al. (2023), while excluded from the meta analysis, reported a risk ratio of 0.62, with a 95% credible interval of 0.44 to 0.83, further backing the meta-analysis results.

(Figure 3) Pooled dropout rate, benzodiazepines versus SSRIs

The pooled effect estimate for the outcome of remission is the most definitive out of the three. While the risk ratio of 1.07 and a 95% confidence interval of 0.97 to 1.19 is quite conclusive, it cannot be considered statistically significant. The p-value of 0.1717 paired together with the results, indicates that despite the fact that SSRIs are most likely to be favoured in the outcome of remission, the true effect size may favour either treatment. However, there was once again no heterogeneity. Thus, it was observed that the results were consistent, with SSRI having a slight advantage, the data was not statistically significant.

(

(Figure 4) Pooled remission rate, benzodiazepines versus SSRIs

As expected, an extremely high amount of heterogeneity and variance was observed in the outcome of adverse effects. The result from I2 was 87.3%, which according to the predefined scale indicates considerable heterogeneity. The pooled risk ratio itself is 1.21 with a 95% confidence interval of 0.86 to 1.72. Because of the large amount of heterogeneity and a random effects model being used to calculate the pooled effect size, the upper and lower limits of the confidence intervals are extremely far apart. For that same reason, the p-value was quite high as well (0.2742). From this we can conclude that while SSRIs seem to have less adverse effects, the results weren’t consistent or statistically significant, making it hard to draw accurate conclusions.

(Figure 4) Pooled adverse effects, benzodiazepines versus SSRIs

Bias in Studies Included in Syntheses

While a bias assessment of the included syntheses was not conducted, we analysed the assessments that were provided by them of their included studies. The study included in Bighelli et al. (2016) was funded by the pharmaceutical company GSK, therefore having a high risk of other bias according to the GRADE risk assessment tool used. The smaller study was also at an unclear risk of selection bias, performance bias, and detection bias, but at a low risk of attrition bias and reporting bias. The systematic review also mentioned that only unpublished data from this study was used, providing no further information. Chawla et al. (2022) stated that “Most of the studies had at least some concerns (70%; 61/87 [from total studies]) or were at high risk of bias (29%; 25/87 [from total studies])”. They also said that most bias was caused by lack of details in the “randomisation and concealment processes”. The study used the Cochrane risk of bias tool for randomised trials (RoB 2.0). Finally, Guaiana et al. (2023) used both RoB 2.0 and GRADE for bias assessment, saying that most studies had either an unclear or high risk of bias due to sources of support and funding. However, they did not separately list the individual studies used in each comparison, so we were not able to find the characteristics and assessment of the studies included in the observed outcome.

Discussion

SSRIs and benzodiazepines have been battling to be the best pharmacological treatment for panic disorder for many years. Unnecessary and untrue bias was expressed towards both treatments with little evidence to support the claims. However, this paper has demonstrated that while SSRIs likely have less adverse effects, benzodiazepines have significantly less dropouts. A possible reason as to why this was observed is that patients are able to see results faster, making them think that the treatment is especially effective. While that inference would not be entirely accurate, it may raise the patient’s morale, improving their overall wellbeing. From this we can conclude that benzodiazepines are more acceptable in the treatment of panic disorder, as patients are willing to potentially tolerate more adverse effects for faster results. The results for remission however, were inconclusive. While SSRIs performed slightly better in both included studies and the meta-analysis, the p-value was higher than the established threshold, indicating statistical insignificance.

This review brought together and compared pooled risk ratios and confidence intervals from three different studies to determine and interpret any found trends or patterns. Afterward, by conducting a meta analysis, combining results from several syntheses, we were able to get the most holistic and comprehensive view on this subject. Only studies which were published less than 15 years ago were included to ensure that false impressions and inferences would not be present due to insufficient understanding of the effects of psychotropic medications on the human central nervous system. Despite these strengths, this review has many limitations. The main ones were the bias present in the studies included in the syntheses and the small sample size. All studies had some kind of bias present, which can easily lead to false data and conclusions. This would explain the large gap between the data reported by Bighelli et al. (2016) and Chawla et al. (2022) in the outcome of adverse effects. The limited number of included studies may have resulted in a narrowed impression and data that would not be applicable in clinical situations. Additionally, none of the studies reported on rate of relapse or other long-term outcomes that could have shown whether treatments have lasting effects enough to make improvements in the patients' lives. Finally, the reviews all had slight differences in their eligibility criteria, particularly the comorbidities section. Different combinations of mental or physical disorders can result in being less responsive to treatment or other nuances that could have caused skewed data. It was also possible, though unlikely, that errors have been made during the data synthesis process resulting in slight inaccuracies.

Benzodiazepines and SSRIs are two of the best treatments that could be offered at this time, but gene therapy for panic disorder, while not yet achievable, could be an option in the future due to the disorder’s epigenetic components. However, in the near future it may be more plausible to observe the long term outcomes of both treatments such as relapse and patient satisfaction or the efficacy of combined psychotherapy and medication treatment. This could provide both healthcare professionals and patients with more accurate and relevant information on the effects of benzodiazepines and SSRIs in the treatment of panic disorder. Further exploring combined or non-pharmacological treatments that were previously mentioned could help us better understand human brain function and reduce patients’ exposure to risks. It has been known that benzodiazepines have many associated dangers, meaning that reconsidering them as a primary treatment for panic disorder could significantly benefit patients. This review attempted to find the superior pharmacological treatment of panic disorder, and while evidence was found and conclusions were drawn, a lot more work needs to be done. The amount of bias found shows that more high quality studies are needed to allow for better conclusions and the small sample size could provide a limited view. Nevertheless, this review managed to confirm and solidify SSRIs as the slightly better treatment for panic disorder.

Data

Raw Data

Adjusted Data

(Table 2) Adjusted Data. Guaiana et al. (2023) reported a Bayesian risk ratio of 0.62 and credible intervals (Crl) of 0.44 to 0.83.

Results

Tables

1. Dropout rate, benzodiazepines versus SSRIs

2. Remission rate, benzodiazepines versus SSRIs

3. Adverse effects, benzodiazepines versus SSRIs

Meta-Analyis Outcomes and Forest Plots

Guaiana et al. (2023) was excluded from the meta-analysis due to it being a study done in Bayesian statistics.

1. Dropout rate, benzodiazepines versus SSRIs, common/fixed effects model

RR 95%-CI Weight(common)

Bighelli et al. 0.5800 [0.3475; 0.9681] 23.6

Chawla et al. 0.5100 [0.3835; 0.6782] 76.4

Number of studies: k = 2

RR 95%-CI z p-value

Common effect model 0.5257 [0.4098; 0.6744] -5.06 < 0.0001

Quantifying heterogeneity:

tau^2 = 0; tau = 0; I^2 = 0.0%; H = 1.00

Test of heterogeneity:

Q d.f. p-value

0.18 1 0.6672

2. Remission rate, benzodiazepines versus SSRIs, common/fixed effects model

RR 95%-CI Weight(common)

Bighelli et al. 1.1200 [0.7895; 1.5889] 8.6

Chawla et al. 1.0700 [0.9611; 1.1913] 91.4

Number of studies: k = 2

RR 95%-CI z p-value

Common effect model 1.0742 [0.9694; 1.1904] 1.37 0.1717

Quantifying heterogeneity:

tau^2 = 0; tau = 0; I^2 = 0.0%; H = 1.00

Test of heterogeneity:

Q d.f. p-value

0.06 1 0.8067

3. Adverse effects, benzodiazepines versus SSRIs, random effects model

RR 95%-CI Weight(random)

Bighelli et al. 1.0300 [0.9213; 1.1516] 53.8

Chawla et al. 1.4700 [1.1772; 1.8356] 46.2

Number of studies: k = 2

RR 95%-CI z p-value

Random effects model 1.2140 [0.8576; 1.7186] 1.09 0.2742

Quantifying heterogeneity (with 95%-CIs):

tau^2 = 0.0552; tau = 0.2350; I^2 = 87.3% [50.3%; 96.7%]; H = 2.80 [1.42; 5.54]

Test of heterogeneity:

Q d.f. p-value

7.87 1 0.0050

Conclusion

According to the data gathered in this review, benzodiazepines and SSRIs would both be acceptable treatments of panic disorder as they each did better than the other in two of the measured outcomes (dropout for benzodiazepines and adverse effects for SSRIs) and performed similarly in the third (remission). While the statistics have shown that SSRIs are slightly superior to benzodiazepines, some of the results were inconclusive. Furthermore, studies noted a high risk of bias which could result in selective reporting or inaccurate data. In the future, more quality evidence could help us make a more definitive conclusion, but until then the choice of medication should be made by the patient and the healthcare provider to ensure that the patient gets the treatment that works best for them.

Citations

- Kessler, R. C., Chiu, W. T., Jin, R., Ruscio, A. M., Shear, K., & Walters, E. E. (2006). The Epidemiology of Panic Attacks, panic Disorder, and Agoraphobia in the National Comorbidity Survey Replication. Archives of General Psychiatry, 63(4), 415. https://doi.org/10.1001/archpsyc.63.4.415

- Association, N. a. P. (2022). Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders. https://doi.org/10.1176/appi.books.9780890425787

- Anxiety: Pharmacotherapy. (n.d.). CAMH. https://www.camh.ca/en/professionals/treating-conditions-and-disorders/anxiety-disorders/anxiety---treatment/anxiety---pharmacotherapy

- Panic disorder: when fear overwhelms. (n.d.). National Institute of Mental Health (NIMH). https://www.nimh.nih.gov/health/publications/panic-disorder-when-fear-overwhelms

- Panic attacks and panic disorder - Symptoms and causes. (n.d.). Mayo Clinic. https://www.mayoclinic.org/diseases-conditions/panic-attacks/symptoms-causes/syc-20376021

- Panic Attacks & Panic Disorder. (2024, June 27). Cleveland Clinic. https://my.clevelandclinic.org/health/diseases/4451-panic-attack-panic-disorder

- Chu, A., & Wadhwa, R. (n.d.). StatPearls. StatPearls Publishing. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK554406/

- MSc, O. G. (2023, July 20). Types of antidepressants and how they work. Simply Psychology. https://www.simplypsychology.org/major-classes-of-antidepressants.html

- Benzodiazepines: How do they work? (n.d.). LNC. https://www.nursingcenter.com/ncblog/august-2022/how-benzodiazepines-work

- Neuronal excitability | the human brain. (n.d.). https://campuspress.yale.edu/humanbrain/neuronal-excitability/

- Haddaway, N. R., Page, M. J., Pritchard, C. C., & McGuinness, L. A. (2022). PRISMA2020: An R package and Shiny app for producing PRISMA 2020-compliant flow diagrams, with interactivity for optimised digital transparency and Open Synthesis Campbell Systematic Reviews, 18, e1230. https://doi.org/10.1002/cl2.1230

- Pek, J., & Van Zandt, T. (2019). Frequentist and Bayesian approaches to data analysis: Evaluation and estimation. Psychology Learning & Teaching, 19(1), 21–35. https://doi.org/10.1177/1475725719874542

- Bighelli, I., Trespidi, C., Castellazzi, M., Cipriani, A., Furukawa, T. A., Girlanda, F., Guaiana, G., Koesters, M., & Barbui, C. (2016). Antidepressants and benzodiazepines for panic disorder in adults. Cochrane Library, 2016(9). https://doi.org/10.1002/14651858.cd011567.pub2

- Chawla, N., Anothaisintawee, T., Charoenrungrueangchai, K., Thaipisuttikul, P., McKay, G. J., Attia, J., & Thakkinstian, A. (2022). Drug treatment for panic disorder with or without agoraphobia: systematic review and network meta-analysis of randomised controlled trials. BMJ, e066084. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj-2021-066084

- Guaiana, G., Meader, N., Barbui, C., Davies, S. J., Furukawa, T. A., Imai, H., Dias, S., Caldwell, D. M., Koesters, M., Tajika, A., Bighelli, I., Pompoli, A., Cipriani, A., Dawson, S., & Robertson, L. (2023). Pharmacological treatments in panic disorder in adults: a network meta-analysis. Cochrane Library, 2023(11). https://doi.org/10.1002/14651858.cd012729.pub3

- Yoon, S., Kim, J. E., Kim, G. H., Kang, H. J., Kim, B. R., Jeon, S., Im, J. J., Hyun, H., Moon, S., Lim, S. M., & Lyoo, I. K. (2016). Subregional Shape Alterations in the Amygdala in Patients with Panic Disorder. PLoS ONE, 11(6), e0157856. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0157856

- Chu, A., & Wadhwa, R. (n.d.-a). Selective Serotonin Reuptake Inhibitors. StatPearls. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK554406/

- Long QT Syndrome | NHLBI, NIH. (2022, March 24). NHLBI, NIH. https://www.nhlbi.nih.gov/health/long-qt-syndrome

- Mejo S. L. (1992). Anterograde amnesia linked to benzodiazepines. The Nurse practitioner, 17(10), 44–50. https://doi.org/10.1097/00006205-199210000-00013

- Benzodiazepines. (n.d.). Government of Canada. https://www.canada.ca/en/health-canada/services/substance-use/controlled-illegal-drugs/benzodiazepines.html

- Zamorski, M. A., & Albucher, R. C. (2002, October 15). What to do when SSRIs fail: Eight Strategies for optimizing Treatment of panic Disorder. AAFP. https://www.aafp.org/pubs/afp/issues/2002/1015/p1477.html#afp20021015p1477-t1

- Office of the Commissioner. (2018, February 5). Understanding unapproved use of approved drugs “Off label.” U.S. Food And Drug Administration. https://www.fda.gov/patients/learn-about-expanded-access-and-other-treatment-options/understanding-unapproved-use-approved-drugs-label

- Bounds, C. G., & Patel, P. (n.d.). Benzodiazepines. StatPearls. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK470159/

- Agoraphobia - Symptoms and causes. (n.d.). Mayo Clinic. https://www.mayoclinic.org/diseases-conditions/agoraphobia/symptoms-causes/syc-20355987

- Agoraphobia. (2025, January 24). Cleveland Clinic. https://my.clevelandclinic.org/health/diseases/15769-agoraphobia

- Lecrubier Y. (1998). The impact of comorbidity on the treatment of panic disorder. The Journal of clinical psychiatry, 59 Suppl 8, 11–16.

- Lensen, S. (2023). When to pool data in a meta-analysis (and when not to)? Fertility and Sterility, 119(6), 902–903. https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0015028223002248

- Grimes, D. A., & Schulz, K. F. (2008). Making sense of odds and odds ratios. Obstetrics and Gynecology, 111(2), 423–426. https://doi.org/10.1097/01.aog.0000297304.32187.5d

- Higgins, J. P. T., & Green, S. (2008). Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions. In Wiley eBooks. https://doi.org/10.1002/9780470712184

- Carlson, R. B., Martin, J. R., & Beckett, R. D. (2023). Ten simple rules for interpreting and evaluating a meta-analysis. PLoS Computational Biology, 19(9), e1011461. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pcbi.1011461

Image Credit

Figure 1

MSc, O. G. (2023, July 20). Types of antidepressants and how they work. Simply Psychology. https://www.simplypsychology.org/major-classes-of-antidepressants.html

Figure 2

Sanabria, E., Cuenca, R. E., Esteso, M. Á., & Maldonado, M. (2021). Benzodiazepines: Their Use either as Essential Medicines or as Toxics Substances. Toxics, 9(2), 25. https://doi.org/10.3390/toxics9020025

Project Banner

Antidepressants: What to Know About Uses and Side Effects. (n.d.). The New York Times. https://www.nytimes.com/2024/04/25/well/mind/antidepressants-side-effects-anxiety-stress.html

Project Image

Tappana, J. (2022, June 23). Everything You Need to Know About Panic Attacks from a Therapist for Panic Attacks in Columbia, MO — Aspire Counseling. Aspire Counseling. https://aspirecounselingmo.com/blog/everything-you-need-to-know-about-panic-attacks

Acknowledgement

There are so many people that I want to thank, but first of all my friends and family. You all have offered me so much support throughout this project, I can never thank you enough. Thank you to Ms. Davis, my school's science fair coordinator, for giving me feedback and teaching me the ins and outs of how to properly do a science fair project. Thank you, of course, to Dr. Cynthia Baxter, Dr. Chad Bousman, and Dr. Sudhakar Sivapalan for answering all of my questions on panic disorder and to Dr. Shahada (University of Calgary, Department of Mathematics and Statistics) for helping with the complicated statistics. Finally, thank you to the authors of the studies included in my review, without your work I wouldn't have had a project.